Previously, in “Becoming a Person,” I wrote, with no great originality:

Previously, in “Becoming a Person,” I wrote, with no great originality:

Incidentally, coherent personhood has been the assumption behind rational government (all but Louis XIV’s Le etat, c’est moi), especially republican democracy. Voting, opinion polls, representation, and constitutions all depend on the assumption that citizens are coherent persons.

The same goes, of course, for all rational organizations. Since Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, we know well enough that working in industrial systems means becoming at least somewhat cog-like. It demands a spiritual shift, so to speak, because one’s ultimate aims, or at least proximate aims, become reconfigured.

Because of my own difficulties at day jobs—seemingly part of the transition from academic life to the workaday—I have been polling friends and family about professionalism. My father wrote, among other generous things:

You must learn to enjoy being useful as a first step.

This is truly a shift of scale, a shift of orientation. My difficulties at work, I realize, stem from the fact of spending the work day looking out for my own interests, and being mainly interested in them. But doing things right means thinking differently. Sitting in the office, my interests have to become one with the office, one with the people I work with. It enables them to trust me and me to trust myself. Professionalism is a technology, in that it makes one useful to others; the person becomes technology.

With the discovery of any new technology there is something gained and something lost. My generation has grown up being acutely aware of this, to the point of cliche. When I first saw the movie Fight Club in high school, nothing could possibly feel more true and obvious than that a successful young professional life, decorated by Ikea and so forth, was empty at its root. Spontaneity gets systematically eliminated. Danger, too. The fundamental facts of existence, death and so forth, are put aside as less significant concerns than the minutiae of office life. The only difference between this and outright slavery is that slaves are aware of their condition; professionals are under the delusion that they are, in fact, self-actualized and coherent persons.

Over at Garzuela, Kurt has been tossing these concerns around as well (beware of obscenity):

Over at Garzuela, Kurt has been tossing these concerns around as well (beware of obscenity):

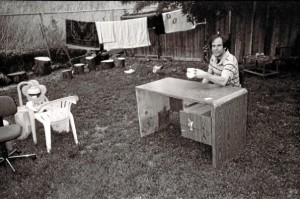

Do you like my new office? I think that it’s good to get some professionalism out of my system, so I can start to live like a real human. Let’s talk about dehumanization of the human race, and how we are being pushed to act more like mindless drones in order to be financially stable in the world? Actually, I think that some people will find it refreshing, and I actually landed the most professional job I’ve ever had yet, as a result of this kind of behavior. Or maybe it was getting this behavior out of my system, that allowed for me to get into my niche. Maybe I should say moist professional job, put hand on top of her head, and slowly guide it toward my crotch. Careful not to let her know that I’m unzipping my pants with my other hand, and getting a sweet ding a ling ready for her.

The obscenity to beware of is a prerequisite of such resistance against professionalism. Just like the fistfights in Fight Club it shocks the system, or shocks the person out of the system.

Yet these things I grew up knowing don’t feel quite known anymore. I’m twenty three years old, seeking my fortune and so forth, and a little professionalism has become required. Without it, I definitely can’t do my job. Without it, I keep messing up in little tasks, letting my personal interests overshadow my functional purpose. Doing the job right demands a little … inauthenticity, though in my life so far, evading professions, I have always denied the possibility of that concept. How, I have thought, can one be other than oneself, or be more or less oneself?

Professionalism demands a line of separation between person and public face, an segregation of spheres so that each might be coherent—all in such a way that invents, for the first time, the dialectic of authenticity. It becomes a question possible to ask: Am I being authentic? Authentic to what?