I could be frantically live-blogging from this year’s American Academy of Religion meeting in Chicago. I won’t, per se. But in a number of places here I have been hearing lots of talk about religious “extremists” and “moderates.” It goes without saying that nearly all of the thousands of AAR attendees—mostly academics in religious studies and theology departments—identify as the latter and, with the exception of certain “radical” social justice causes to which we might belong, consider the former as the “them” that we study or seek to undermine.

But then there is a catch. As anybody subjected to at least a name-dropping familiarity with Hegel (or more sexy contemporary exponents like Zizek and Derrida) knows, the two sides of any such binary imply each other, and indeed, rely on each other to know themselves. Moderation, that is, only makes sense to talk about when we have some idea of extremism to distinguish it against. This is a nice point to make in critical theory discussions, but it immediately gets lost in every other context, particularly when there is a scary extremism (e.g., terrorists) to be ruthlessly eliminated by well-meaning moderates.

The new atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett gave a short talk yesterday called “Public Education, Knowledge, and Visions for Non-toxic Religion.” Despite the Templeton Foundation-sponsored glossy fliers and the booking of a massive ballroom, there were far more empty seats than peopled ones. He took the opportunity to make his proposal for compulsory teaching about world religions in K-12 curricula, including home schools. The idea is that if everyone has to be aware of the basic facts of other religions, extreme forms of religion will disappear, since they can’t abide even knowledge of other religions. What Dennett didn’t say at the AAR but is clear from his books is that he hopes this proposal will spell the end of religion as a whole.

The new atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett gave a short talk yesterday called “Public Education, Knowledge, and Visions for Non-toxic Religion.” Despite the Templeton Foundation-sponsored glossy fliers and the booking of a massive ballroom, there were far more empty seats than peopled ones. He took the opportunity to make his proposal for compulsory teaching about world religions in K-12 curricula, including home schools. The idea is that if everyone has to be aware of the basic facts of other religions, extreme forms of religion will disappear, since they can’t abide even knowledge of other religions. What Dennett didn’t say at the AAR but is clear from his books is that he hopes this proposal will spell the end of religion as a whole.

To most AAR folks, this last step would be a counterintuitive one. What many (of us) dream of, in fact, is a world populated lovingly by nice religious moderates who abhor violence and intolerance while emphasizing love, sustainable lifestyles, and diversity. They are educated about each other and revel in difference as well as the cosmopolitan values everybody holds in common.

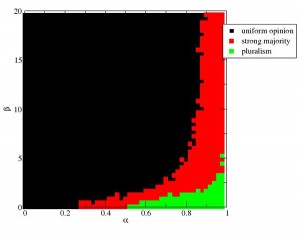

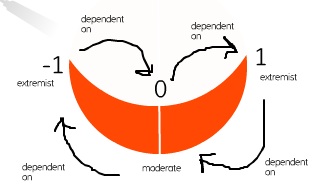

A new study, published a few days ago in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (vol. 11, no. 4 9), gives some interesting evidence supporting Dennett’s assumption. It is called “Can Extremism Guarantee Pluralism?” Using a computer simulation, the authors (two Italian physicists, Floriana Gargiulo and Alberto Mazzoni) modeled a community of software agents who exhibit a range of opinions between two extreme poles. The agents could interact with each other and change each other’s opinion. Extremists were those less willing to have their opinions changed by others, while moderates were more open to it. Imagine a simplified version of American politics: extreme Democrats and Republicans on each end, with moderates in the center, open to hearing others’ ideas out. They tinkered with the simulation in different ways to see how it reacted to different kinds of interaction between the agents.

A new study, published a few days ago in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (vol. 11, no. 4 9), gives some interesting evidence supporting Dennett’s assumption. It is called “Can Extremism Guarantee Pluralism?” Using a computer simulation, the authors (two Italian physicists, Floriana Gargiulo and Alberto Mazzoni) modeled a community of software agents who exhibit a range of opinions between two extreme poles. The agents could interact with each other and change each other’s opinion. Extremists were those less willing to have their opinions changed by others, while moderates were more open to it. Imagine a simplified version of American politics: extreme Democrats and Republicans on each end, with moderates in the center, open to hearing others’ ideas out. They tinkered with the simulation in different ways to see how it reacted to different kinds of interaction between the agents.

The results are interesting. When like-minded agents weren’t permitted to cluster but instead forced to interact with others, the whole simulation turned into homogeneous mush. No diversity. All the simulated agents ended up agreeing. When extremists were allowed to be isolated from others, they ended up forming islands in what was still homogenous mush. Any way you slice it, a world dominated by moderates means no or no meaningful diversity.

The only way the simulation could produce stable diversity, it turned out, was when extremists were able to both isolate themselves and interact with the larger community, influencing moderates. Extremists enabled moderates to know, thereby, what doctrines they were moderate about, and thus to maintain some diversity in their interactions with other moderates in contact with a different set of extremists.

Dennett’s fellow new atheists, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, have alienated many by maintaining that religious moderates are in fact guilty for the crimes of extremists because the views they hold moderately legitimate those who hold similar views in more extreme forms. The JASSS study suggests that there is some truth to that claim. But just as disturbing, it points out how lines of influence go both ways; extremists and moderates both fundamentally enable each other.

Social psychologists, such as Jonathan Haidt, have lately been exploring how political preferences are informed by certain psychological dispositions that are more or less fixed in a person’s psychology. Thus it seems to be no accident that some people end up holding to quite rigid beliefs while others are more flexible. The range appears to be built into the normal spread of human variation—perhaps to secure the adaptive benefits of diverse opinions. For, as this study shows, diversity depends on interaction among both the fringes and the open-minded.

On the ground, this dialectic has consequences that may seem a little distasteful. If we moderates at the AAR are to enjoy diversity and openness, we might think twice about dedicating ourselves to eradicating extremisms as such. The psychological evidence suggests we probably won’t be able to anyway. And, in one area of life or another, most of us can’t help but find ourselves being extremists too.

(This reminds me of an earlier post about South Park.)

Comments

One response to “All in Moderation?”

[…] outrage, actually, is pretty consistent with what Daniel Dennett has predicted would happen if classes in world religions were required in schools. It is a threat to intolerance. […]