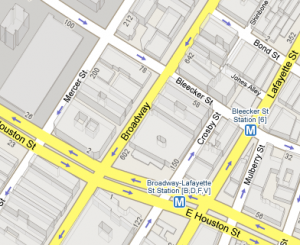

Last night, while waiting for a friend at the corner of Lafayette and Bleeker, I learned that to stand at a busy corner near a Manhattan subway entrance means becoming a directions machine. In the course of half an hour, maybe eight people asked me for directions. I’m a guy with a pretty good sense of direction, so in every case I knew the answer, and I told them. Then, at the end, I got out the map that I was carrying in my sack all along. Turns out, half the directions I gave were at least somewhat wrong. Worst of all was this exchange where I was asked where Mercer Street is, and I pointed north up Lafayette, having some memories of Mercer close to NYU. But a woman walking by shouted out, No way, it’s down south of here. I said, Fine. Well of course, a few minutes later I learned Mercer is parallel to Lafayette, two blocks to the west. Both of us, in all our certainty, were dead wrong.

Last night, while waiting for a friend at the corner of Lafayette and Bleeker, I learned that to stand at a busy corner near a Manhattan subway entrance means becoming a directions machine. In the course of half an hour, maybe eight people asked me for directions. I’m a guy with a pretty good sense of direction, so in every case I knew the answer, and I told them. Then, at the end, I got out the map that I was carrying in my sack all along. Turns out, half the directions I gave were at least somewhat wrong. Worst of all was this exchange where I was asked where Mercer Street is, and I pointed north up Lafayette, having some memories of Mercer close to NYU. But a woman walking by shouted out, No way, it’s down south of here. I said, Fine. Well of course, a few minutes later I learned Mercer is parallel to Lafayette, two blocks to the west. Both of us, in all our certainty, were dead wrong.

The realization hit me like, what… the punch that killed Houdini? If I spread all those incorrect (though innocent, rather inconsequential) factoids, what more have I missed without knowing I missed it? Not least, because of the mythical importance giving accurate, precise directions has in my paternal line. But more immediately troubling, as a writer, what accidental falsehoods have I set down and published?

Since first grade, when this kid named Seth fooled me up and down all the time, I’ve known that just about always I’m the most gullible person in the room. The result of being an only child, perhaps. Tell me anything and I’ll believe it, unless you really, really overdo the sarcasm. Or unless I’m massively prepared by some aloof posturing. Probably this is why I ended up getting into studying religions—I have a peculiar fascination with getting inside the beliefs people adopt. Constantly in this work I feel myself being drawn into them, then sneaking out. Viscerally, being gullible feels like the mechanism at work in my bad direction-giving as well. It is the same willingness to believe the first thing that pops up as a possibility.

Wikipedia has a great list of cognitive biases, many of which are pertinent here and have better, more scientific names than “gullibility.”

I recently spoke with a reporter at The New York Times, who in many ways seemed to have the opposite dispositions. His background is as a big-city police reporter, investigating crooked crooks and crooked cops. Now, having been placed on the religion beat, the habits of suspicion he learned on the police beat carry with him. He told me that when he sees a lot of big-shot pastors, he says they look an awful lot like the mob bosses he used to know. It’s hard to get past that, he said, but it does push him to dig deeper, to ask more questions, to get to the bottom of it all.

My tendency is otherwise. I’m usually content with the first things I discover about an issue, or with the bad guys’ public rhetoric. For me the fun is in the interpretation, in crafting the raw material into a story. But the more I do this work of writing about others, the more respect I have come to have for the facts. Particularly writing for the internet, where interpretations are a dime a million, facts are what can turn a story upside down. Or “evidences,” as the 19th century theologians used to say—until Darwin came along, at least.

So I’ve been trying to initiate myself into the cult of suspicion—suspicion of my own beliefs and of the claims that others make. A suspicion that will force me to ask more questions, suspect my own impressions, and go beyond the veneer of lies that covers most everything in public life.

At the same time, though, there is something peculiar in the study of religion that makes gullibility a virtue. When you’re dealing with religions, there is always an important truth to be found even in the coarsest lies. These aren’t truths that would be admissible in court, perhaps, but they’re human truths nonetheless. What they convey is part of the religious state of affairs, and it cannot be ignored. To see those truths, buried as they are in plain sight, it helps to be willing to try any old belief for size. It helps to be gullible.

Giving decent directions, however, is quite different.

Comments

4 responses to “Giving Bad Directions”

Enjoyed this post, Nathan.

It gives me much glee to read a piece entitled “giving bad directions” that discusses religion’s imperfect relationship with reality. I also associate religion with a loose respect for facts and a requisite degree of gullibility, but probably in a different sense from you. 🙂

Maybe your “gullibility” is more a hermeneutic of generosity.

Suspect maxim of the moment:

You cannot suspect others usefully unless you first suspect yourself.

Yup, it’s the “unknown unknowns” that get us. A “follow the money!” policy is good to fall back on…

BT: Money? Where’s the money?

Eli: no, generosity is too conscious. This is a cognitive bias. More like what you have in mind!

Joel: right on. And then at some point you’ve got to figure out where to stand up for yourself. Sometimes I’ve failed in that, too.

Thanks for your words, friends.