The following is an essay by sociologist of religion Darren Sherkat, one of the main players in my recent article about the foundations behind religion surveys. Sherkat here focuses on the question of response rates, which isn’t much discussed in the articles about these surveys, including mine. The truth is, he argues, the most-publicized religion surveys have response rates too low to be reliable. The General Social Survey, with a much higher response rate, is far more reliable. And it makes even clearer the bias—whether intended or not—toward reporting high levels of religiosity in many of the other surveys. I offer this as an additional perspective, not necessarily to express fervent agreement (I’ll have to explore this more myself).

The following is an essay by sociologist of religion Darren Sherkat, one of the main players in my recent article about the foundations behind religion surveys. Sherkat here focuses on the question of response rates, which isn’t much discussed in the articles about these surveys, including mine. The truth is, he argues, the most-publicized religion surveys have response rates too low to be reliable. The General Social Survey, with a much higher response rate, is far more reliable. And it makes even clearer the bias—whether intended or not—toward reporting high levels of religiosity in many of the other surveys. I offer this as an additional perspective, not necessarily to express fervent agreement (I’ll have to explore this more myself).

In March of 2009, the most important survey of American religion was released, but nobody noticed. While media pundits and religious activists tout the findings from surveys with very low response rates and minimal comparability to other studies, the 2008 edition of the National Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey became public access sometime in March. I’m a regular user, and I couldn’t tell you precisely when the new GSS became available. There was no press conference, and this will be the first you’ve heard of what’s really going on in American religion.

The cover of USA Today and almost ever other publication presented findings from the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) data, which is a nice little study, for some purposes. Last year, findings from the Pew data generated a media circus, and before that, it was the Baylor survey. What the ARIS, Baylor, and Pew studies have in common are exceptionally low response rates. Few of the targeted respondents actually complete the interview–about 20%, perhaps a little higher in ARIS, Baylor, and Pew. In contrast, the lowest response rate ever achieved in a GSS survey has been 70%, and the 2006 and 2008 surveys garnered 71% of targeted respondents.

Studies cannot be compared when they use different questions, so the pissing match between pundits and investigators of these studies has no scientific merit. The question asked in ARIS is unique, and interesting. But, you cannot compare the distributions of the ARIS question on religious identification to distributions of religious ties based on other ways of asking the question. Given the exceptionally low response rates of the Baylor, ARIS, and Pew data, legitimate scholars should be embarrassed for having made claims about population parameters which cannot be discerned with reasonable certainty.

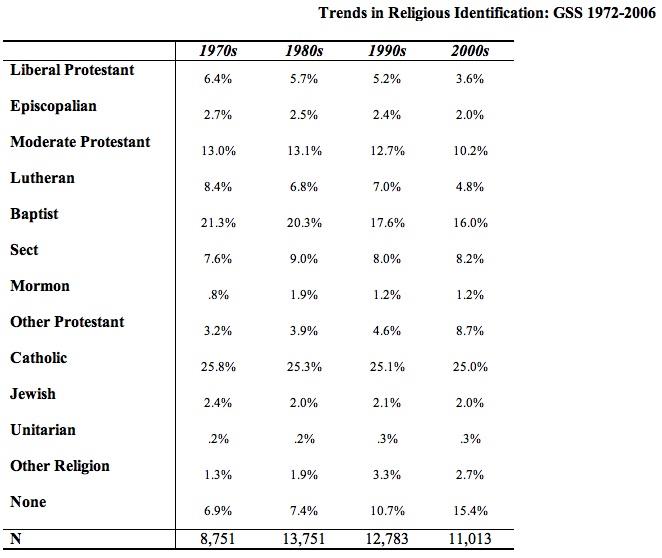

What is really going on? GSS data provide a much more accurate summary of the trends based on comparable data collected over time. Below is a table cumulating evidence from the GSS surveys from each decade. As you can see, the percentage with no religion has increased dramatically; from under 7% in the 1970s, to over 15% in the 2000s. Non-Christians move from under 11% of respondents in the 1970s, to over 20% of respondents since 2000. Notably, in the just released 2008 GSS data presented below in Figure 1, 16.5% of GSS respondents reported no religious identification, and 21% are non-Christian. This is a higher proportion of non-identifiers than is reported in either the ARIS or Baylor studies, probably because non-identifiers are more likely to be non-respondents in studies with low response rates.

Further, contrary to ARIS and Baylor, high quality data from the GSS show that the proportion of sectarian Christians (the proper term for what journalists and activists call “evangelicals”) is in decline. Most of the decline comes for Baptists, who are shrinking fast. But, other sectarian groups peaked in the 1980s.

Religious identification is declining in the United States. Anyone who claims that irreligion is not growing is simply wrong. And, claims that conservatives continue to grow are based on exceptionally weak evidence.

Should we believe ARIS or Baylor? The answer is neither. The GSS shows no growth among sectarian Protestants since the 1990s, and Baptists (the largest sectarian group) are in considerable decline.

One in five Americans rejects religious identification. The 2008 GSS shows that 20% of Americans believe that the Bible is a book of Fables (up from under 14% in 1984, the first year the GSS asked that particular question), and that 18% do not believe in a “god” (up from 13% in 1988, the first year that particular question was asked).

Religion isn’t going away, but rejection of religion is growing. Americans have long been forced to accept the hegemony of Christianity, but that hegemony is breaking down, and secular Americans cannot be ignored by anyone serious about contemplating the vagaries and trajectory of American culture.

Comments

One response to “Making Sense of American Religion”

The word religion is used in such a broad way as to be almost meaningless. Just for fun let us distinguish Type A and Type B. A is actually a social club to relieve loneliness, provide some feeling of identity, and some fuzzy comfort. Real energy goes into capitalism. Type B religious feeling affects one’s lifestyle and world outlook. If one belongs to a peace religion, for example, one really is peaceful and really works for spiritual peace at some depth. Nominal religious identification does not tell me very much.