Critics of militarism have to make sense of its humanity, to find a place for it, to honor it.

Critics of militarism have to make sense of its humanity, to find a place for it, to honor it.

This gray afternoon, with a friend, I went to the U.S.S. Intrepid, the Essex-class aircraft carrier-turned-museum on the west side of Manhattan. Dubbed “The Most Inspiring Adventure in America,” it’s an opportunity to tour through half a century of clever combat airplanes and nautical contrivance. I knew them all pretty well from childhood. The planes, the missiles, the bombs, the protocols. How unsettling to see those elegant monsters on the carrier deck there, against the backdrop of Midtown, in a quiet and peaceful retirement.

When the Intrepid museum reopened last year, several other friends of mine were there protesting. I was going to be but at the last minute wasn’t able. I wanted to. So I felt uneasy the whole time, paying my student admission fee (with an expired ID), to this grand monument to American warfare. And how could we not make a monument? The machines are amazing. And much more pressing is the courage, the lives, the tiniest details of the people who fought in them.

When the Intrepid museum reopened last year, several other friends of mine were there protesting. I was going to be but at the last minute wasn’t able. I wanted to. So I felt uneasy the whole time, paying my student admission fee (with an expired ID), to this grand monument to American warfare. And how could we not make a monument? The machines are amazing. And much more pressing is the courage, the lives, the tiniest details of the people who fought in them.

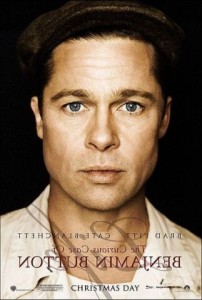

After that I went to see The Curious Case of Benjamin Button with yet another friend. With the previews came Kid Rock’s promotional video for the National Guard, mixing rock ‘n’ roll with stock cars with benevolent, courageous soldiers. It’s called “Warrior.” (More on the implications of that term.)

On the one hand it saddened me. It glorifies thoughtless belligerence. He sings, “So don’t tell me who’s wrong or right when liberty starts slipping away.” And there’s a picture of a column of Humvees rolling through the desert with machine guns mounted atop. It’s a tragic contradiction. Liberty, we are to understand, is something so unmistakable that one no longer needs to distinguish right from wrong when soldiering in its name. That’s no liberty I’ll recognize, and certainly not one I’ll fight for.

But the propaganda had its charms as well. There are scenes of soldiers helping where a natural disaster struck. And there’s one moment where some gun-toting soldiers stop to make friends with brown-skinned kids in a dusty village. Kid Rock sings, “They call me ready to provide relief and help, I’m wherever you need me to be.” I could sign on for that! As long as the weird requirement about tossing out ethical reflection about the use of force in the name of “liberty” weren’t part of the deal.

In Benjamin Button itself, there’s a war scene. Benjamin’s on the crew of a little tugboat that has been commissioned by the Navy during World War II. There’s a machine gun mounted up top, and that’s it. Suddenly, they find themselves face to face with a German U-boat that just sunk a transport full of people. Bodies float in the water. What do they do? They charge the U-boat. They ram it. In the process, nearly everyone on board gets killed by enemy machine guns. It’s an absurd and gruesome event of course, but also an incredible act of sacrifice, and one done without hesitation.

These three pieces of glorified war cannot be taken at their word. Each, in its way, leaves the most horrible, and at least equally essential, parts of its story untold. But there is truth in each too, in even the honor it seeks to portray.

Benjamin Button has a lot of beautiful moments that tug at the heartstrings to the point of being crassly manipulative. One of these is at the beginning. There’s a story told about a clockmaker who builds a clock for a train station in the years after World War I. When the clock is unveiled, he reveals that it turns backward. The reason, he announces, is to turn back the clock on all the boys we lost in the war, including his own son, so that they might have full lives after all. And then, there is a brief scene, played in reverse, of a charge in that Great War: out from the explosion that kills a uniformed boy back, back to his last moments of life, back home, back to his leaving his family. None of it had to happen. None of it should have.

Benjamin Button has a lot of beautiful moments that tug at the heartstrings to the point of being crassly manipulative. One of these is at the beginning. There’s a story told about a clockmaker who builds a clock for a train station in the years after World War I. When the clock is unveiled, he reveals that it turns backward. The reason, he announces, is to turn back the clock on all the boys we lost in the war, including his own son, so that they might have full lives after all. And then, there is a brief scene, played in reverse, of a charge in that Great War: out from the explosion that kills a uniformed boy back, back to his last moments of life, back home, back to his leaving his family. None of it had to happen. None of it should have.

There must be a way to honor such sacrifices as war brings out in people while abhorring the pointless insanity that occasioned it, abhorring it so completely that it can never possibly happen again.

Comments

6 responses to “Militarism and Heroism”

“Critics of militarism have to make sense of its humanity, to find a place for it, to honor it.”

“There must be a way to honor such sacrifices as war brings out in people while abhorring the pointless insanity that occasioned it, abhorring it so completely that it can never possibly happen again.”

I’m not sure. I’ve been increasingly influenced by the work of John Howard Yoder and other Christian pacifists, and I feel no need to “honor” militarism. I am compelled to abhor violence; I don’t know if I can abhor the large-scale war while honoring those carrying out the war (at any level). It seems an inconsistent position: to commit to a life of peace, yet to “honor” those who participate in the violence of war. “Honor” comes too close to glorification (whether or not that is true in the realm of ideas, it is too often true in actual practice). I think it possible that continuing to honor the people who participate in war is a significant part of perpetuating a militaristic culture, and thus goes against the desire to abhor war “so completely that it can never possibly happen again.” Stopping the honor of militarism might be a significant step toward stopping war.

So not “honor.” But sadness, sympathy, empathy, and love. Perhaps another word entirely. For those who sacrifice much, for those who lose much without ever having the choice.

Just my thoughts. Peace.

For me patriotism is an outmoded idea.

It is a long legacy of tribalism that tries to help us feel that we are somebody. One of the great carriers of tribalism is the so called “Old Testament.” It is a long war story honored in millions of homes.

Quentin, I hear you! I’ve actually been planning on going back to the book of Joshua, which tells of the Israelites’ conquest of the land they believed they had been promised. It is so true—those martial books have offered centuries of justification for warfare.

Joe, thank you. Great thoughts. I really sympathize with your position, that by all means necessary the willingness of our culture to exact violence needs to be curbed. I think what drives my reflections, however, is the belief that there is truth in every position, in every experience. In the Gandhian framework for nonviolence, at least, this is what brings us to nonviolence in the first place. During the Vietnam War, the anti-war movement hated soldiers so much that it did great violence to them. It left a generation of veterans adrift in a society that was ashamed of them.

What I’m looking for here is a way to create a peace that’s big enough to include the massive human infrastructure that the military represents in our society. Peace with dignity for all, so to speak. A society that soldiers and weapon makers and all the others can want as much as peacenik bloggers.

Additionally, we have to recognize that many of the same traits that people exhibit as soldiers (self-sacrifice, teamwork, loyalty, commitment) are the very traits that will be required to create a society that is both nonviolent and truly just. We can draw on some of the values learned in war to sow peace. One need only recall William James’s seminal “Moral Equivalent of War.”

“Honor” may be the wrong word, because it has so many connotations that associate it with the most insipid forms of violence (e.g., honor killings, duels, etc.).

[…] Ticker Nathan on Militarism and HeroismQuentin Kirk on Militarism and Heroismjoe fischer on Militarism and HeroismMilitarism and Heroism | […]

Great piece. I’m always looking to refine my language about ‘honoring’ soldiers while abhorring what they do.

Nathan, I can’t tell you how happy I was to discover that another Christian shares my understanding of the reverence for other human beings made in God’s image. War has long been a difficult issue for me. I actually started blogging after 9-11 because suddenly war seemed like a serious moral issue that could not be treated as such– in churches, among friends, or even in the public sphere. I am so grateful for you attention to this issue. Also, if you would send an email to my address listed above, I will explain a little project I am working on which I think would be right up your alley.

(PS Most of my anti-war blogging was on my website, totalitarianism today. Like many, I maintain more than one blog..)