It began with the advice of a federal judge in 1949. If you’re not going to follow United States law and register for the draft, he told the group of Alabaman Quaker farmers before him, “get out of this country and stay out.” So they did. In 1951, along with several dozen family members and fellow Friends, they sold what they had in the States and flew down to a remote mountaintop in Costa Rica. Only a few years before, the country had abolished its military, so there was no threat of conscription. They didn’t know the language or how to farm in a tropical climate. The early years weren’t easy, and the community splintered several times; some moved to Canada, and others became Seventh-day Adventists. But when longtime peace activist John Trostle came to visit their town of Monteverde in 1962, he tells me, “I thought I’d discovered Shangri-La.” There was a school, a cheese factory, and an arts scene on the verge of flourishing. By 1974, he and his wife Sue moved to the community themselves.

It began with the advice of a federal judge in 1949. If you’re not going to follow United States law and register for the draft, he told the group of Alabaman Quaker farmers before him, “get out of this country and stay out.” So they did. In 1951, along with several dozen family members and fellow Friends, they sold what they had in the States and flew down to a remote mountaintop in Costa Rica. Only a few years before, the country had abolished its military, so there was no threat of conscription. They didn’t know the language or how to farm in a tropical climate. The early years weren’t easy, and the community splintered several times; some moved to Canada, and others became Seventh-day Adventists. But when longtime peace activist John Trostle came to visit their town of Monteverde in 1962, he tells me, “I thought I’d discovered Shangri-La.” There was a school, a cheese factory, and an arts scene on the verge of flourishing. By 1974, he and his wife Sue moved to the community themselves.

The Quakers inadvertently gave rise to an ecotourism mecca. From the beginning, they set aside a large portion of rainforest in order to protect their watershed from pollution—a purely practical decision for a town of farmers. But a few decades later, as biologists learned of it and came to study wildlife living there, the community took up the cause of conservation. Wolf Guindon, one of the original settlers who had spent time in federal prison for resisting the draft, led the charge to build their watershed into the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve, which keeps a sizeable chunk of Costa Rican rainforest in perpetuity for visitors and researchers.

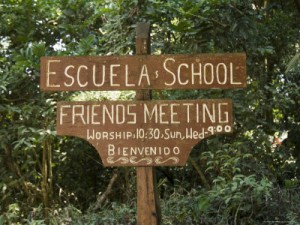

Meanwhile, their school has brought up generations of local Costa Rican children with perfect English and a knack for North American sensibilities. By the mid-’80s, tourists followed on the heels of the biologists, and a hospitality industry exploded. Today, backpacker hostels and luxury restorts line the road that the Quakers once had to navigate by oxcart. The original settlers are ambivalent about the endless stream of visitors, which brings jobs to their neighborhood but disturbs its quiet.

The Monteverde Quakers’ quiet is one solution to the problem of militarism. They didn’t come to be beacons of anything, and they shy away from attention. “The people who started this community don’t think of themselves as something special,” Sue Trostle explains. Most of their free time gets consumed by the endless supply of committee work that Quaker community life demands. But their children don’t have to fear a draft, and not one colon of their taxes goes to pay for an army. They’ve built the cheese factory into a collective owned by the local dairy farmers who supply it. Martha Moss, who moved down with the Trostles, brought the Alternatives to Violence Project to Costa Rican prisons. The school doesn’t proselytize Quakerism among its students, but it teaches peace. Militarism florishes now more than ever in the United States. They couldn’t prevent that. But they showed that they could build a life apart from it and flourish.

Marcy Lawton is a biologist who studies birds. She began coming to Monteverde in 1974 as a graduate student at the University of Chicago to do her research, and now she owns a home there with her husband. They’re members of the Quaker Meeting. Her work focuses on brown jays, which are famous for their remarkable acts of altruism—”Quaker birds,” she calls them. Most of the time, her jays are peaceful, community-oriented, and remarkably generous with each other. But after years of observation, she began to notice wrinkles in their behavior. When birds grow up without enough apprenticeship from their elders, they behave differently. They hoard, fight, and even commit infanticide. The more years a bird spends in a nourishing community, she has learned, the more a brown jay’s behavior comes to resemble generous, mysterious love.