In the Catholic Church, it is traditional to celebrate a saint not on the day of his or her birth, as we do for American presidents, but on the day of death. Part of the reason is that so many of the saints were martyrs, whose status depends precisely on the way they died. They gave themselves up to some heroic and often grotesque demise in the name of their savior. Doing so, actually, puts a person on the fast track to sainthood.

In the Catholic Church, it is traditional to celebrate a saint not on the day of his or her birth, as we do for American presidents, but on the day of death. Part of the reason is that so many of the saints were martyrs, whose status depends precisely on the way they died. They gave themselves up to some heroic and often grotesque demise in the name of their savior. Doing so, actually, puts a person on the fast track to sainthood.

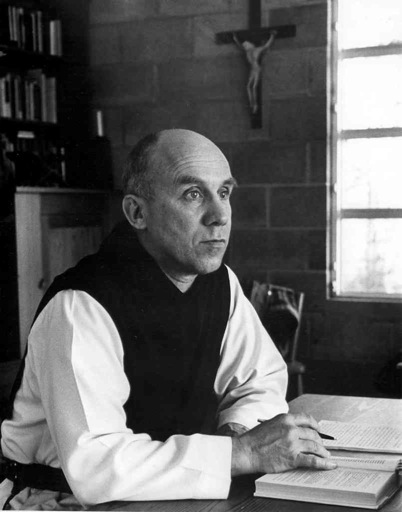

Thomas Merton—a man known to his fellow monks as Father Louis—hasn’t come to be regarded as a saint, though still now his spirit works miracles in the lives of so many people. His death was like much of his life: almost astonishingly mundane. In Bangkok, Thailand for an interreligious summit, he was accidentally electrocuted to death by touching a fan after stepping out of the bath. But, such as it was, that happened exactly 40 years ago today, so today I will celebrate his feast.

Like the finest saints and the most interesting sinners, Merton took a peculiar route through life. Born in France to an American mother and a British father in 1915, he had a mobile childhood between France, England, and Long Island. Eventually he enrolled at Columbia University, where, as a talented writer, he fell in with a fantastic and worldly literary scene. It was while there, and mostly despite his friends, that he grew more and more interested in the Catholic Church. In 1938, he was baptized at Corpus Christi Church on 121st Street. By 1942 he became a Trappist monk at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky and never stopped.

From his monastery, and from the hermitage he later moved to, Merton wrote a tremendous yet precious supply of books, essays, letters, journals, and poetry. He became a kind of chaplain to many great artists, activists, and spiritual leaders of the 1960s. His mind changed, wrestled, and questioned. Once he asked the Dalai Lama in all earnestness if he should become a Buddhist (His Holiness said no), and once he fell in love with a woman. Merton’s books, now published by an unlikely pairing of New York high literary houses and pious Catholic presses, bear these struggles in themselves under the veneer of tranquil prose. Inevitably, they change lives.

I read The Seven Storey Mountain, his early conversion memoir, when I was 17. A few weeks later, I ran off to spend some time at the nearby Trappist monastery in Berryville, Virginia. There, I met Brother Benedict Simmonds, another New York literary alum whom The Seven Story Mountain had, years before, dispatched to the monastery as well. We began a lasting friendship, which continues through letters, visits, and spectacular Xeroxes from the monastery library. The following Easter, I too was baptized a Catholic with Benedict as my sponsor.

I read The Seven Storey Mountain, his early conversion memoir, when I was 17. A few weeks later, I ran off to spend some time at the nearby Trappist monastery in Berryville, Virginia. There, I met Brother Benedict Simmonds, another New York literary alum whom The Seven Story Mountain had, years before, dispatched to the monastery as well. We began a lasting friendship, which continues through letters, visits, and spectacular Xeroxes from the monastery library. The following Easter, I too was baptized a Catholic with Benedict as my sponsor.

Just the other day, I spoke on the phone with a dear friend living across the world. In some attempt to understand me, I suppose, she bought the Mountain years ago but only recently began reading it. Now, half serious, she says she wants to be a monk too. “Go, stubborn talker,” wrote Merton in “The Poet, to His Book”:

Find you a station on the loud world’s corners,

And try there, (if your hands be clean) your length of patience:

Use there the rhythms that upset my silences,

And spend you pennyworth of prayer

There in the clamor of the Christless avenues:And try to ransom some one prisoner

Out of those walls of traffic, out of the wheels of that unhappiness!

Merton’s legacy does more than send New Yorkers to the monastery. Last night, I was reminded of this anniversary at a meeting of Catholic war resisters, people who sustain their energy for difficult and costly action through the fruits of Merton’s contemplation. He is the patron saint—or, rather, mere human being—for that community of hermits who find by searching and whose peace comes in the struggle that causes no harm.

Things and people goodbye

It is not that I prefer

The singleness of death

Where no companions are,

Yet things and “you” and “I”

The “he” the “she” the “they”

Must all go off alone

In common, not to be—

And not in company.

– untitled, 1964

Comments

One response to “The Feast of Father Louis”

To my surprise, this piece has been picked up by the Dutch site News4All. Take a look. It’s the first time I’ve been translated, to my knowledge.