I wrote what follows at the beginning of the year, upon first arriving in New York. I sent it in to a contest, and it didn’t win, so I thought it might be fair game to share here. It is called, “The Voyage of the Beagle.” I’m actually not sure if this is the final draft because I can’t seem to open the final file.

People take evolution to mean different things.

Now, at the end of what has already come, I take it to mean New York—my present voyage of the Beagle, going on day by day, not knowing what I do. There is a dream I keep having; never at night, for at night my dreams are taken by practical matters like finding a place to live and an income. The dream I mean, interpolated over such ordinary, ordinary life, looks like this:

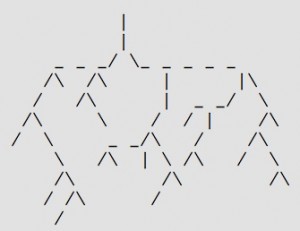

An upside-down tree, as if uprooted and inverted by the giant inhabitants of skyscrapers, with each person and thing around me, and me, forming its ends. We differ in song, shape, and size, displaying our differences like cocks. On the trains, all the variety of human sounds comes muffled through too-loud headphones.

On the trains, we are pushing and pulling in crowdedness, in flesh. The same people combine and splinter, one city and different neighborhoods, one train and different stops. Like that, combining and isolating, we speciate and hybridize, forming new branches in the tree. Sometimes all of a sudden, sometimes gradually. On my bike, weaving between the taxis and soaring over the bridges, the branches curve and split and open.

Technology is everywhere, on people of every sort. I want more of it myself with a newly unapologetic need. It makes me see how Henry Miller could have hated the place so much, reserving for it his worst vitriol. He seemed to know he was alive as long as he could find new words of condemnation for New York. But I have been to his hideouts—to Paris, to Big Sur, and to Greece—and his hatred only makes me desire this place more. A strange thing happens every day here, the way it wouldn’t quite or couldn’t in Virginia or Rhode Island or California, where I have lived before, where so far I have been forming. In the buildings and the strangers (stranger after stranger!) there is the occasional pregnant teenager, I inside of her and she inside of me, whose missing period has yet to come. She knows not what she bears within her.

But maybe that is because I moved here so recently that I have acquired nothing except for food and a single book about Charles Darwin’s birds. Life, in so little time, hasn’t had time to distinguish itself from dreams. And what seems so hard to believe, but what should be so simple, is that it matters (for evolutionary purposes above all) that now, twenty-three years old if a day, I am in New York.

But now I am the city boy

who doesn’t understand

the struggle

between nature and man.

Found taped to the side of a subway car.

* * *

A year younger than I am now and two days after Christmas, Charles Darwin set out on the H.M.S. Beagle in 1831. He joined on as gentleman companion to the captain, Robert FitzRoy, a melancholy firebrand with missionary ambitions for the South American savages. For almost five years, they sailed around the world making maps for the British admiralty, exploring strange new worlds. Along the way, Darwin collected creatures and observations, writing home to his family and to the English scientific societies, sending along crates full of taxidermy.

What he saw in those years took a lifetime to unravel and interpret. Two years after his return, the first picture of an evolutionary tree appears in his notebooks. The Origin of Species, which exposed the theory of evolution to the public, was not printed for another twenty years. In the meantime he kept on refining, hiding, fearing the consequences of his ideas, and suffering from debilitating illness. He held the voyage in his mind, not permitting it to complete itself.

What he saw in those years took a lifetime to unravel and interpret. Two years after his return, the first picture of an evolutionary tree appears in his notebooks. The Origin of Species, which exposed the theory of evolution to the public, was not printed for another twenty years. In the meantime he kept on refining, hiding, fearing the consequences of his ideas, and suffering from debilitating illness. He held the voyage in his mind, not permitting it to complete itself.

Yet what did it the voyage hinge on? The smallest things, the slightest branches of an inverted tree, growing by the falling of gravity. It depended on a letter that arrived in Shrewsbury, and on Captain FitzRoy’s ridiculous phrenological instincts. Darwin wrote in his autobiography, many years later:

The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career; yet it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle offering to drive me 30 miles to Shrewsbury, which few uncles would have done, and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose.

So much depends upon the precious and ridiculous, on what supports the branches of the hanging tree.

Darwin returned from the voyage a celebrity among the genteel naturalist set. Always “ambitious to take a fair place among scientific men,” his Autobiography recalls that after reading a congratulatory letter at a port of call, he scaled the mountains of Ascension Island “with a bounding step and made the volcanic rocks resound under my geological hammer!” What he did with the subsequent decades, of course, made him the most significant of all his peers. Though by then confined to bed with a repulsive illness, Darwin became a hero and a villain, revealing the world in the same stroke that he vanquished a certain charm ascribed to it.

This discovery, this evolution, weaves together the insignificant and the grandiose. Darwin describes a creation that happens by a sequence of accidents; creatures’ chance variations are vetted by surrounding circumstance, by the island or city they find themselves in, that they depend on to survive. A few millimeters on a bird’s beak or the peppering of a moth is enough to be a difference. Then Darwin learned grandiosity from Charles Lyell, the geologist whose books he carried with him on the Beagle. Lyell saw from the present into imperceptible deep time. The layers of immovable rocks could tell how they’d once moved, and were moving, through a world whose scales of time hardly notice the lives of people. We’ll have to be strangers if we are to understand time. We’ll have to go to foreign places, big cities, open oceans, and silent caves to know anything about our familiar homes.

Still more than a decade before publishing the Origin, Darwin could write of his journey as if it were uncompleted. Compared to the later Autobiography‘s tone, the voice sounds cautious rather than triumphant. He insists on the voyage’s real mundaneness, the passing elation met by routine unpleasantness particular to life on an ocean, or on any unfamiliar adventure:

No doubt it is a high satisfaction to behold various countries and the many races of mankind, but the pleasures gained at the time do not counterbalance the evils. It is necessary to look forward to a harvest, however distant that may be, when some fruit will be reaped, some good effected.

The whole voyage was a point of departure, the beginning of an event that had not yet come. On the sea, so in the city.

* * *

I have been to New York before. My father would come here often when I was little to see operas, and occasionally he would bring my mother and me along—I squirmed and resisted. I remember a Thanksgiving Day parade, with all the giant balloons overhead. I remember the hotel where we always stayed, across the street from Lincoln Center, and I remember the tiny rooms where I heard the sounds of taxis all through the night.

These memories come in discrete segments, glimpses of trips that themselves were short, separated by no-man’s-lands of time in between and by forgotten things. Another hotel room, during high school, where my girlfriend and I tried to sleep away the distance between us while our friends groped and moaned in the other bed. In college I would end up in New York, for one reason or another, when my life felt fallen apart or my heart was broken. My heart has broken at least three times in New York, all so far before actually moving here. In college, for consolation, I learned my favorite churches, which became pilgrimage spots—Fifth Avenue Presbyterian, St. Bartholomew’s, and Corpus Christi in Morningside, among them.

The memories lie scattered, and as such they return when I see the places that now recall them. Their sequence is random, mutating with each recollection, though their foundations, I have no choice but to believe, actually happened.

Scientists have learned that each time memories are remembered they are reinvented, touched by the mark of the present. There is a chemical that, when introduced, can stop the act of remembering present events. If it is given to a rat while getting an electric shock, the rat won’t remember to avoid the shock next time around. But if a rat got the shock without the chemical, and has learned to avoid the hot wire, that memory can be erased. Inject the same chemical while showing the wire to the rat, reminding it of the shock, and from then on it forgets to be afraid. Memories depend on how they are tended—recollection opens the door to mutation, an imperfect rebuilding influenced by the conditions of the present.

In mutation Darwin found the diversity of life, from which new possibilities come. Miscopying and recombining, new genetic codes emerge and try their luck at life. Remembering, we ejaculate, sending forth, leaving ourselves fuller and emptier. As people, what we know of ourselves is what we know of our memories. Dividing, remembering, recalling, and forgetting—all in the shape of a tree—I come to inhabit my own species.

It could be quite appalling that Darwin considered his voyage of the Beagle incomplete in itself. Isn’t a voyage a feat of cosmic ordination that should stand as it was, in need of nothing else? Still awaiting the Origin‘s publication, those memories were unfulfilled and waiting for their harvest; only after could they be “the most important event” in Darwin’s life. Now, as my voyage of the Beagle is only beginning—or ending—in the city, my own memories fulfill themselves as accessories. Scattered as they are, they congeal in combinations of the present, according not to how they occurred but to how they are now recalled. They go on to form and shape each other, later memories now acting on earlier ones in defiance of chronology and common sense. They make a tree, dividing and inventing, beginning from a common root and branching off in new combinations, spread across the landscape of the city and dividing it into parts.

In her famous attack on the modernist planners, Jane Jacobs set forth an evolutionary ecology of the city; she wrote it while living in mid-century Greenwich Village. After finishing the book on Darwin’s birds, I borrowed hers from a friend. It brings to life the strangers that surround me here—they are the city’s guardians and its possibilities. Our anonymous eyes watch over each other. They graft the worlds they make for themselves onto the public landscape. This is what separates the species of city from that of towns and villages, where strangers mean trouble and upset the balance. The multitude of strangers is why a strange thing happens to me every day. I keep seeing old friends amidst the strangers: a miraculous event. Or hearing a new song or being invited to a place I’d never been before. The certain probability of these events, which turn my mind to improbable memories, lies exactly in the uncertainty, the strangeness of strangers. Jacobs’s strangers fill my imagination as I walk on these mortal streets, making heroes of the passers-by.

In the city as in Darwin’s evolution, the power of explaining erodes. The hope of easily explaining oneself, or delivering an apology, slithers away from the tree of knowledge. Explanations last for only an instant of the deep time on either end of the present, and the present that needs them keeps rebuilding its needs like new out of old dreams and old genes. This is why Jacobs insists that we should not build our cities around what we know now, planned and measured monotony in every place, but for the inventiveness of future multitudes. Her heretical argument for diversity is orthodox, Darwinian ecology.

These moments of my voyage, unfinished wholes, look toward their unseen conclusion and their unseen beginnings. Like ghosts. Still in pieces, I feel exuberantly whole.

This false memory once taunted me, also mapped over the inverted tree. I have an older sister (whom I do not have), and she talks down to me:

“I am older than you,” she explains. I hear the words without being able to touch them. “You are younger than me. Before you were I was.” And this sort of thing, which she says lightly in the heavy air.

“Once you did not exist. Nobody had even thought of your name or what you would look like,” she continues. “Until I did, Mama did, Dad did.” She stops and picks up a ball from inside my crib, where I am helpless.

“But there was nothing before me.”

* * *

I came here for a reason: because Mary Elston is here. So many other people too, but first of all because of her. I spent the last year and a half in California by the ocean unable to look at the ocean without missing my Mary, still in Rhode Island, where I had left her. Now I have come, living out of suitcases and sleeping on the floors of friends, exclaiming about the pregnancy of the moment, and together we feel like a glass house.

After missing each other for so long, the closeness is overwhelming—we might each be made of only the other’s dreams, clothed in skin. We get tired and annoyed between moments of happiness. Between my drifting, her working, her family, and all our scattered obligations, all the time that remains for us together has been sleep. So we argue about that. I say something terrible, somehow. Another unspeakable thing.

The other day we had a great bout in the street, by 20th and Broadway. I would shout one thing and she would shout another, in hushed shouts, wet by tears. You’ve seen it if you’ve seen New York. In this place of everyone all at once, there are lovers fighting everywhere, and Mary and I are among them too, in the rain, left behind, in the maze of streets with only a map. There was no use protecting our voices from the hundreds of passing strangers, remembering that they are our safety. Compassion can be found in them, in their unflinching passing, their undisturbed faces. One time or another, they have been here too before returning to normal, self-collected anonymity as strangers. If someone had stopped and tried to say something, to help us, we would have felt truly alone.

After that Mary and I shared a cautious hot chocolate in the cafe of the housewares store across the street, trying to be kind again, trying to remember how. And now that was the last time I saw her. I’ve called, and I’ve written, and this has happened before. Yet now is a new mutation, a new recollection of the same old complaints that we can never seem to settle. A new opportunity for mutation, and a new feeling-out of our evolutionary landscapes. With every recollection, recall, is the possibility for forgetting.

It was then that I realized: speciation—the creation of a new species in nature—is an act of forgetting.

Speciation is at once the central and the remotest part of Darwin’s theory. The possibility of creating new species by variation and natural selection, he argued, is what makes all the multitudes of creatures possible. Yet in The Origin of Species, Darwin could cite no example of a species observed originating. Following the habit of Lyell’s deep time, he assumed that such processes are so painstakingly slow that they cannot be observed in human lifetimes. The closest Darwin thought he could come was his examination of selective breeding for dogs and livestock.

Since then, researchers have found ways to notice signs of speciation among creatures. It appears to happen in different ways, whether by geographical isolation, by population bottlenecks, or by the discovery of a new niche. In any case, a population that was once a single species divides to become two or more. First, the diverging groups forget that they are able to hybridize—to produce offspring together—and keep to their own. Over generations, this isolation causes the groups to vary so much that they become physically unable to hybridize. Their bodies, as well as their minds, forget what once united them. Though experienced by no one, I imagine a wrenching horror in being pulled apart like that, gene from gene, creature from creature, relative from relative, memory from memory.

In the last century, these processes have been observed much more closely than Darwin was able to imagine. Careful studies of populations during times of shifting ecology—catastrophic weather or the introduction of a new species, for instance—make natural selection plain to see. It turns out that species are far less stable than people have usually imagined. They are preserved less by their own inertia than by the fragile ecology that they depend on to survive. In the event of cataclysm, sudden changes can occur, from mass extinctions to explosions of new forms. The scale of these events can be global, or they can be so isolated as to go unnoticed. My book on birds says that “for all species, including our own, the true figure of life is a perching bird, a passerine, alert and nervous in every part, ready to dart off in an instant.”

The anxiety of speciation runs through this silence Mary and I have now made. Ready to dart, awaiting the unfolding of ecology between us. I am waiting to move my boxes from her house to my new apartment, as she waits to shift downtown. An opportunity to dart away? The tremendous tragedy of separation sounds comical in its enormity, its bare factuality: speciation is the failure to hybridize. We would not create young. We would not create a world together. We would not be together. But we could come out of this silence in any of a million forms, so we are waiting to see which and working on our helpless plans.

Again, and I can’t even begin to say how: it matters that I am in New York.

Comments

3 responses to “The Voyage of the Beagle”

Thank you

Even though the above comment is spam I’ll accept it as a compliment.

This is a beautiful piece, I really enjoyed it. Perfect for the moment as I have just arrived back in ny…