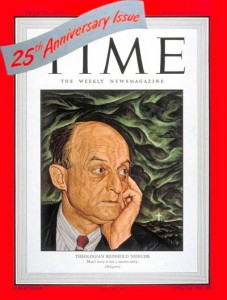

During the years leading up to World War II, there was no deeper thorn in the side of Christian pacifists—by whom I mainly mean members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a community founded in the first months of the previous world war—than Reinhold Niebuhr. Having been formed as a pastor in working-class neighborhoods of Detroit, he led the FOR in the early ’30s. But he quickly began to question the wisdom of a radical commitment to nonviolence. As Hitler rose to power and the horror of his rule became apparent, Niebuhr doubted that the Christian conscience had any other option than containment by force. After the war, he became a defender of the U.S.’s Cold War posture against the Soviet Union. Today, his legacy has been cited by those eager for an end to the last decade of American hubris—Obama described him as “one of my favorite philosophers.” Though he asserted the need for armed conflict against hideous wrongdoing, he was motivated by the same skepticism of utopian thinking that left him no hope for the use of violence in the service of high ideals.

During the years leading up to World War II, there was no deeper thorn in the side of Christian pacifists—by whom I mainly mean members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a community founded in the first months of the previous world war—than Reinhold Niebuhr. Having been formed as a pastor in working-class neighborhoods of Detroit, he led the FOR in the early ’30s. But he quickly began to question the wisdom of a radical commitment to nonviolence. As Hitler rose to power and the horror of his rule became apparent, Niebuhr doubted that the Christian conscience had any other option than containment by force. After the war, he became a defender of the U.S.’s Cold War posture against the Soviet Union. Today, his legacy has been cited by those eager for an end to the last decade of American hubris—Obama described him as “one of my favorite philosophers.” Though he asserted the need for armed conflict against hideous wrongdoing, he was motivated by the same skepticism of utopian thinking that left him no hope for the use of violence in the service of high ideals.

In order to hone my recent thinking on peace and conflict, which have mainly been informed by Gandhian approaches, I’ve been working through Niebuhr’s 1940 essay “Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist,” collected in Robert McAfee Brown’s Essential Reinhold Niebuhr, published by Yale University Press. These are some reflections from an initial reading, thinking with Niebuhr and seeing where he takes me.

The Law of Love and the Condition of Sin

Niebuhr centers this discussion around the meaning of Christian love, which of course radical pacifists use as part of the basis of their position. He points out:

Christianity is not simply a new law, namely, the law of love. … Christianity is a religion which measures the total dimension of human existence not only in terms of the final norm of human conduct, which is expressed in the law of love, but also in terms of the fact of sin.

Sin is the reality of his “realism”—the cosmic fact that Christianity does not eliminate but embraces, reconciles, and forgives. Yes, violence is a sin against love, but that sin, too, has its place in Christian humanity. A few pages later, he states it another way: “The significance of the law of love is precisely that it is not just another law, but a law which transcends all law.”

The law of love does not represent a particular political strategy. Jesus didn’t baptize tactics, he baptized sinners. Love, therefore, is a posture within a sinful world, not an escape from it. The pacifists, Niebuhr would say, have taken a Pharisaical position, placing a norm of behavior above all else, including God.

One might distinguish, perhaps, between a law and a commandment. A law is a limit placed on actions, essentially coercive in nature. A commandment, of which Jesus said love is the highest, is something different. Commandments upbuild us, urging us toward creative action, in and through a world that includes both law and lawlessness.

Pacifism vs. Nonviolent Resistance

Next in the essay, Niebuhr asks how biblical modern nonviolence theory really is. In the first half of the twentieth century, peaceniks preached peace but generally lacked a method. But by the end of World War II, most believed they had found one in the work of Gandhi. The method of nonviolent resistance perfected in the Indian independence movement quickly began to take hold in the civil-rights struggle of black Americans. (For Niebuhr, as well as for Martin Luther King, the chief source was FOR member Richard Gregg, who lived with Gandhi in India before writing his classic The Power of Non-Violence.) Many Christian pacifists believed that Gandhi was in some sense a fulfillment of Christ’s promise.

Yet does Jesus’s scriptural example really have anything directly to do with Gandhian resistance? Jesus exhibited no interest in the overthrow of an unjust social order, beyond noting that its temples would crumble and its poor would always remain. He stood up for all sides of political divisions—centurions, tax collectors, oppressed Jews, and dejected prostitutes. Sure, he advocated taking blows without complaint, and did so himself; but he also spoke of swords and lashed out at merchants. Jesus’s witness was mainly pacifist, but it would be an exaggeration (and a disappointment) to say that this constituted Jesus’s essential message. Ascribing to him a Gandhi movement would be a stretch.

In the later books of the New Testament, the situation changes little. The text that has seemed to me the fullest in its resources for nonviolent resistance is 1 Peter (“For it is better to suffer doing good, if suffering should be God’s will, than to suffer for doing evil.” – 3.17), which appears to be a primer for martyrs-to-be. A technique is discussed, but there’s no indication that it should be applied beyond the particular circumstance of persecution. And it certainly takes little interest in bringing about change in the social order. God, not resistance, is the epistle’s cause of the change to come.

Niebuhr is very right to question the certainty of some that Christianity proscribes a particular tactic for dealing with political conflicts. It doesn’t. Still, that isn’t to say nonviolent resistance is decidedly un-Christian. It is a tool by which Christians may act Christianly. Just because Jesus did his healing through hand-waving magic tricks doesn’t mean (unless you’re a Christian Scientist) that Christians shouldn’t use hospitals to alleviate the suffering of others. Indeed, the establishment of hospitals for the poor was one of the great achievements of early Christianity, and continues to be.

Nonviolent struggle for justice is a way to enact the commandment of love, and a very good one. But it isn’t the way, so far as concerns the Christian legacy.

Christian Realism

The sum of Niebuhr’s thought is often described as a Christian “realism.” It takes seriously the inevitability of sin and selfishness in human affairs, then seeks a set of social arrangements which provide a modicum of justice and the freedom for Christian witness to flourish.

Violence and war have a place in this. They have a certain necessity for him, though Niebuhr hardly had great confidence in their capacity for do-gooding. An adventure like the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which sought to transform a crumbling society into a model democracy through transformative violence, was hardly something he could get behind. But an intervention in Darfur against a coordinated genocide, more likely yes.

The trouble with Niehbur’s realism is its tendency toward fatalism. Indeed, he seems to realize this in the essay—it ends with a passage that appreciates the witness of pacifist Christians to the radical message of the gospel. Their voice, he accepts, can remind those who bear arms not to put too much trust in them. Niebuhr’s pressing concern, though, is to discredit those—like his former fellows in the FOR—who would call any willingness to fight wrongdoing with force a heresy.

But the consequences of fatalism are horrific in their own right. The nihilistic bombing raids that Allied bombers exacted on Germany and Japan reveal how complacency about the inevitability of war can easily slide into unbelievable brutality. And, immediately after, the reckless escalation of military industry in the Cold War only narrowly escaped self-immolation and delivered a condition of permanent, addictive militarism on the economy of the United States. Can these simply be written off as the inevitable wages of sin? Or shall we try harder to prevent such things from happening in the future?

Peacebuilding

“Blessed are the peacemakers,” Jesus said. Let us take this at face value, and forgive me for not probing the Greek etymologies (if English is good enough for Jesus, someone once said, it’s good enough for me). There is blessing in making peace, not simply in taking blows or constructing performances of resistance. Making peace can mean many, many things, depending on the time and place. Perhaps God leaves the means up to us.

Where I think the realist Niebuhr falls short is in the resources he provides for constructive peacebuilding action. He offers one set of negations—pacifism and passive resistance—against another—defensive war and a political order not dictated by religious commandments. For this reason he has become a darling lately for both neocons (like Michael Novak and David Brooks) against passivity abroad and planned economies, as well as liberals (like E.J. Dionne and Barack Obama) against military adventures and boisterous imperialism. But what is he for? What can he inspire us to do?

After putting a Niebuhr book down, one should be sure to go in search of those active in peacebuilding—fostering dialogue, providing for basic needs, erecting the infrastructure of justice—to counteract the excesses of his good sense. Efforts like these can be both pacifistic and realistic, both nonviolent and responsive. They fill in what he seems to leave out.

But that doesn’t mean peacebuilding—any more than pacifism or warfare—should become our religion, or be distilled as the essence of a religion. It is a tool of love, and a good one, though not to be mistaken for love itself.

Comments

2 responses to “Niebuhr, Pacifism, Realism, Peacebuilding”

A friend wanted me to draw out the passage where I said, “Nonviolent struggle for justice is a way to enact the commandment of love, and a very good one. But it isn’t the way, so far as concerns the Christian legacy.” Let me try:

In the essay I’m kinda purposely vague about where Niebuhr ends and I begin—the reason being that I’m still trying his ideas on and seeing where they go. But I think I can stand by the passage you quote.

It doesn’t mean that violent struggle can be an expression of Christian love—I’ve studied this argument in the past (http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7407.html) and can’t bring myself to accept it. I’m not sure if Niebuhr would or not. In this essay I deal with here, he seems to understand war as a necessary and tragic expression of sin. I’m not sure whether love would enter the picture except perhaps where self-sacrifice is concerned.

I also mean to agree with Niebuhr that Christianity doesn’t equal Gandhian political struggle. Yes, there are resources in the Bible to support it, but there are also resources to support genocide. Jesus’s own efforts seem much closer to anti-political pacifism than political resistance. The point is: I think nonviolent resisters have to take fuller responsibility for their commitments. They can’t just say, “This is what Christianity tells us all to do, so we have to do it.” Instead (and I think this is actually more empowering), they should say, “I am a Christian, and I have come to the conclusion that this is the right thing to do, and I find deep resources to guide me in it in my faith.”

The only trouble—and this was Niebuhr’s crucial point—they can’t go around saying that everyone not doing Gandhian resistance isn’t Christian. That latter quotation I give above—the same thing could be said by a soldier. Point is, Christianity is, and should be, something bigger than nonviolent resistance. Just as it is, and should be, bigger than the religious right’s personal morality agenda. Otherwise, either becomes an idol. The Christian understanding of sin and law does not allow us to confuse our methods with our faith as a whole. But we should not allow that fact to prevent us from making our case to Christians and others about why we believe nonviolence is such an important thing to practice, and such a Christian thing. It’s a subtle difference, but an important one. It forces us to take a fuller responsibility onto ourselves for our political activities, and it affects how to talk to and think about other Christians who disagree with these.

What hardly anyone seems to understand is that in 2009 everything is now completely different, and that the old ways wont work any more—in fact they never really did.

This reference explains why.

http://global.adidam.org/books/not-two-5.html

Plus this reference from the same book, gives a very sobering assessment of the state of the world, pointing out that the two world wars were effectively the destruction of global civilization, and that it has been downhill ever since—despite the seeming technological developments which have relieved the burdens of many people.

http://www.beezone.com/AdiDa/reality-humanity.html

Plus this image from a completely different source shows in stark detail the relationship of the church to the Western imperial project.

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/Orozco/panel13.html

Sourced from The Pentagon of Power by Lewis Mumford. A book which described the origins and historical development of the Western Mega-Machine and its drive to total power and control.

ALL of the negative patterns and developments that Mumford warned us about in the book, have come true, and on a scale that he could have hardly begun to imagine.