Perhaps philosophy today has taken its cue from a world that believes ideas need not be taken seriously. They can be replaced, the policy goes, with stuff like enjoyment, the market, and values. Or else, ideas are simply a subset of those. I myself have argued at times that philosophy might simply be reducible to friendship. In The New Republic, Adam Kirsch has just written a powerful attack on the academy’s embrace of Slavoj Zizek, whom Kirsch makes out to be a dangerous fascist clown in favor of everything the 20th century taught us not to do. The apotheosis of this embrace, in my eyes, was seeing a paper delivered to an evangelical audience at the American Academy of Religion meeting this year (the panel started with a prayer), which excitedly used Zizek as a tool for resurrecting evangelical politics. If a hip, handsome evangelical pastor can love Zizek, anyone can. And by taking the clown for a responsible thinker, have we forgotten that ideas have real, decisive consequences?

Perhaps philosophy today has taken its cue from a world that believes ideas need not be taken seriously. They can be replaced, the policy goes, with stuff like enjoyment, the market, and values. Or else, ideas are simply a subset of those. I myself have argued at times that philosophy might simply be reducible to friendship. In The New Republic, Adam Kirsch has just written a powerful attack on the academy’s embrace of Slavoj Zizek, whom Kirsch makes out to be a dangerous fascist clown in favor of everything the 20th century taught us not to do. The apotheosis of this embrace, in my eyes, was seeing a paper delivered to an evangelical audience at the American Academy of Religion meeting this year (the panel started with a prayer), which excitedly used Zizek as a tool for resurrecting evangelical politics. If a hip, handsome evangelical pastor can love Zizek, anyone can. And by taking the clown for a responsible thinker, have we forgotten that ideas have real, decisive consequences?

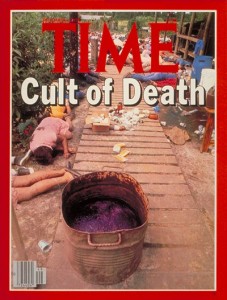

Meanwhile, in honor of the 30th anniversary of the Jonestown mass suicide, I’ve been struggling to know what ideas can do in the face of horror. This, with Jonathan Z. Smith’s insistence at the end of his essay, “The Devil in Mr. Jones,” that the whole promise of the human sciences rests on their hope of giving an answer to what happened there in 1978:

For if we do not persist in the quest for intelligibility, there can be no human sciences, let alone, any place for the study of religion within them.

In the comments over at Larval Subjects, there is a pretty good start to a reply to Kirsch’s essay.

First, the article fails to mention Zizek’s oft-repeated statements about choosing the “bad alternative” as a way of shifting the very co-ordinates of the debate. In other words, the aim is not to advocate the “bad” position as the review suggests, but rather to shift the terms of the debate and reveal the hidden assumptions that underlie the debate. … Second, nowhere does the review outline Zizek’s arguments against liberal democracy.

What Kirsch does do, though, is show that Zizek is a man at play. While walking the walk of a successful bourgeois philosophy professor, he manages to talk the talk of a violent revolutionary, calling for a return to Leninism and Maoism and the destruction of liberal democracy. Whole traditions like Christianity and Judaism are reducible to nugget-like principles, which make them and their adherents candidates for eradication if necessary. If Kirsch is right, Zizek has forgotten that ideas have serious consequences and thinks, quite nihilistically, that he can toy with them however he wants and however he can attract attention. If Larval Subjects is right, Zizek believes we need to be shaken into a new willingness to take ideas seriously as offering alternatives to the world order. Even if the latter is so, however, how much will Zizek take responsibility for the horror his proposals might create?

I am no Zizek, but the method I am trying to develop in the study of religion has resonance with his. I try to toy with ideas wherever they go, whatever their consequences may be. Though I suspect that creationism is false and possibly dangerous, for instance, in my research I am most interested in uncovering the truth in it. Following J. Gordon Melton, I refuse to label even the most troubling new religious movements as “cults”—and therefore as fundamentally different from mainstream established religions. It is, in this sense, a kind of a-moral method. In the process, I rest my faith on a principle of intellectual nonviolence: seek the truth everywhere and in the end goodness will prevail. Like Zizek, according to the Larval Subjects reading, I want to shake my readers out of their own assumptions and worlds, into the possibility of another.

But, after watching the excellent PBS documentary on Jonestown, I was struck by the feeling that my method had real shortcomings in the face of this event. What can I do but sympathize and explore? My way of taking Rev. Jones’s ideas seriously would be to find the truth and resonance in them, rather than opposing every resemblance to them, wherever it might appear. Do I have to go further? This comes to mind, especially, as I write about Harun Yahya, the Turkish creationist who may or may not be guilty of some rather Jones-like crimes.

Does “taking seriously” mean a wagging finger against dangerous ideas or a reckless foray into them?

Comments

18 responses to “Are Ideas Serious? (Zizek in Jonestown)”

TRB: “Even if the latter is so, however, how much will Zizek take responsibility for the horror his proposals might create?”

Kvond: This is a good question, and I suspect is key to the moral position of the entire jouissance project he conducts. His position would no doubt be much like the professor took toward his murderous students in Zizek’s much loved Hitchcock’s film, “Rope” (1948), horror at the literalization of one’s words and theories. I remember attending a lecture of his some time ago, and asking him a question which assumed the extreme consequences of his theoretical analysis of Jerusalem as a petite object a, his horror, real horror to the very nature of the question, was genuine.

This does not mean that such jouissance horror should not be generated by ideas, frameworks, analyses. But the subject who engages in them should own up to the consequences of their pleasure.

http://kvond.wordpress.com/

Thanks for your comment. I enjoyed looking at your site.

It is a tough balance. As I see it, the more responsibility we inject into the practice of philosophy, the more totalitarian it will become, paradoxically, as the powers that be to go great lengths to avoid any risk-taking in the development of ideas. On the other hand, a philosophy free of responsibility would be both pointless and impossible.

I think somewhere or other in the past I have stated my own relief that in the United States intellectuals are only taken somewhat seriously (when compared to Europe). It gives us the chance to play with bizarre ideas, while at the same time, occasionally, reserves the opportunity to enact them politically.

While walking the walk of a successful bourgeois philosophy professor, he manages to talk the talk of a violent revolutionary, calling for a return to Leninism and Maoism and the destruction of liberal democracy.

Which is, of course, not even remotely true – Zizek is neither a professor nor does he advocate to return to Leninism – this is the main problem with Kirsch’s essay, most of it is factually incorrect, even if he manages to raise some good questions.

Nathan: “As I see it, the more responsibility we inject into the practice of philosophy, the more totalitarian it will become…”

Kvond: I suppose that would depend on the difference between “held responsible for” and “taking responsibility”. The responsibility I imagine is much closer to the Lacanian notion of “owning up to”, possessing, or living the synthome. Perhaps this leads to totalitarianism. That would have to be argued. From my point of view, it is the disavowal of jouissance which is distinctly, but not exclusively, totalitarian.

Nathan: “I think somewhere or other in the past I have stated my own relief that in the United States intellectuals are only taken somewhat seriously (when compared to Europe). It gives us the chance to play with bizarre ideas, while at the same time, occasionally, reserves the opportunity to enact them politically.”

Kvond: Please direct me to these “bizarre ideas”, experimenting American intellectuals. Perhaps I am blinded, but I have seen nothing come out of America that remote compares with the experiments in thought done in Europe in the last 30 years. If anything, American thinkers seem to be good at synthesizing and domesticating Continental thought.

Again though, I may have entirely missed the American thinkers you are applauding.

http://kvond.wordpress.com/

[…] course, the problem is, as Nathan asks, what happens when irony is not understood as irony? […]

Mikhail Emelianov, I’m willing to believe you’re right. I haven’t read much of Zizek—just The Puppet and the Dwarf years ago, Iraq, and then a handful of essays here and there. But the Wikipedia page does describe him as “a professor at the European Graduate School.” And my word was a little off; not returning to Lenin but repeating him. Again, as I expressed in my essay, I am open to the possibility (the “Larval Subjects” position above) that this is not to be taken literally.

kvond, I appreciate the Lacanian vocab. I am in totally virgin territory with Lacan, even more so than with Zizek. It sounds like we’re on the same page, though, with “responsibility” and “owning up to.” In both, it seems, there is a certain necessity as well as a certain danger. There are parallels here to debates about relativism vs. absolutes as well as individual vs. collective ethics. Each side in these has its slippery slope and charting a course through them takes care—a word I might even mean in the Heideggerian way.

As for my other remark, maybe I should have been more careful in my haste. “United States,” “bizarre,” and “intellectual” all aren’t the right words. Yes, of course, from the perspective of Continental philosophers such as this group (I am something of a purposeful novice in that scene), all that Americans have contributed is some possibly productive synthesis and domestication. Having studied Continental philosophy in the U.S., I know the feeling. But there are all kinds of other thought out there. I spend considerable time exploring American religious ideas, especially from new religious movements (such as Rev. Jones’s People’s Temple). There you have something unquestionably American, often bizarre, though often not quite intellectual. On the intellectual side, though not necessarily so bizarre, there are folks like those listed in this recent Chronicle article, such as David Rieff (along with his parents), Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker, Martha Nussbaum, Christopher Hitchens, Mark Lilla, and Francis Fukuyama. I’d add Cornel West, Richard Rorty (along with the entire pragmatist tradition), Charles Taylor, Edwin Hutchins, Daniel Dennett, Talal Asad, Noam Chomsky, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and so on. Working in the U.S., more or less. This stuff is different from Zizek, Lacan, and the rest, but it is thought all the same, and they say things that are much their own, things with meaningful influence. Trying to find an American Zizek or Foucault doesn’t quite make sense because the function of philosophy in the society is different. Figures like that, you’re right, just don’t seem to appear.

But actually, I didn’t mean to sound so chauvinistic. I’m not one to parade American thought over and above everyone else’s. Many of those thinkers I mentioned, anyway, had their training abroad or were born there, and so much the better.

Anyway, interesting discussion. Thanks for checking back!

When you describe him as a “successful bourgeois philosophy professor” who is somehow pretending to be a revolutionary, then in that sense, he is not a professor, he’s technically a “researcher” at University of Ljubljana which allows him to publish and travel, were Zizek to take a permanent position somewhere with tenure and all, then I could see your point. But it’s a technicality – what’s so wrong with being a professor and write about revolution, which Zizek, of course, does not in a way Kirsch is presenting him. As for “repeating Lenin” – you make it sounds as though it is an accusation, or that it is sufficient in itself to simply say: “Look, he’s talking about repeating Lenin” and that’s enough. Many scholars are recently drawing attention to Lenin and his vision of the Russian Revolution. Take the collection like Lenin Reloaded that includes essays from Badiou, Eagleton, Jameson, Balibar, Negri among anothers, no one is accusing them of being deadly jesters. As you yourself point out, you haven’t read much of Zizek, and while I get you point about ideas having effect and all that, how can you then evaluate Kirsch’s attack as “powerful” as opposed to say “misinformed” or “superficial”?

A critique is certainly “powerful” if it has the power to decisively influence the majority who are not experts, not only if it pleases those who are. “Powerful” doesn’t necessarily mean correct, and it often doesn’t. (See, for instance, my earlier discussions on powers.) If you would prefer not to engage others who are not experts in what you’re interested in, choose a thinker who less actively attracts attention than Zizek.

I am glad, however, that you are able to tell me ways in which Kirsch’s article is inaccurate!

Look, I don’t mean to be accusing Zizek of something he’s not doing. But I’ve read enough of the guy to know that, probably more visibly than any one else right now, he is drawing attention to the cabal of revolutionaries whom today’s political Left has noticeably abandoned. You can’t deny that he says things purposely to ruffle feathers, quite more successfully than the others you mentioned. I think I am justified when I inquire into whether such jestering with figures so identified with atrocity is a good idea or not.

The statement you keep banging me with is a paraphrase of Kirsch. I explicitly qualified this by saying, “If Kirsch is right…” I tried to write in such a way that is aware of my own ignorance while not letting that bar me from trying to make sense of what I do know.

As I read the article, there are two main, somewhat hidden, charges leveled against Zizek. The first is that he is a celebrity, and an intellectual one at that (always a suspicious thing to be, something whose effects are not always foreseeable nor controllable…who knows what kind of effect this GUY is going to have?); the second is that he is not horrified by the proper things, which is essentially an aesthetic, if sociologically legitimated question: Is your pleasure (jouissance) in the right place…are you enjoying the right kind of things? Honestly, I think the biggest problem people have with him is the former and not so much the latter. His notoriety, and his theoretical affinity with the dominated media culture (he swims like a fish in it), is threatening to those “intellectuals” doing REAL work locked within academic institutions and mindlessly repetitive, incrementally progressive, journals.

I am glad, however, that you are able to tell me ways in which Kirsch’s article is inaccurate!

I am but it would certainly take a lot of my time and I really don’t care that much about disproving Kirsch – there’s a whole host of comments appearing with specific matters misrepresented by Kirsch, I’m sure you can read them – for example, comment to the article itself give a lot of information. Disproving Kirsch, however, is probably a thankless job, he’s already made up his mind long before any possible arguments – you’ve read the piece, didn’t you?

Look, I hate to come across as confrontational and all, I’m not really – I just think that for someone who is aware of Zizek, as you say, you shouldn’t be jumping on Kirsch’s wagon so willingly as to paraphrase an obvious misrepresentation and use it as if it is true, even if you qualify it… I most object to the tone of the article, not its content, one doesn’t have to be an “expert” in Zizek to see multiple holes in the logic of the piece. But then again the sensitivity to the issue of violence is the subject of Zizek’s recent work and therefore the way Kirsch freaks out about a possible defense of certain types of violence only proves Zizek’s point. In addition to that, liberal democratic violence, such as torture or police brutality, are not being discussed very often, so even if Zizek’s completely off and wrong about everything, maybe this will at least make people ask serious questions…

Well, whether or not Kirsch changes his mind, refutations would be of use to others. And yes, I did read the piece.

kvnod, the accusation on grounds of celebrity is an interesting one. Certainly something we’ve seen a lot lately—especially the strange equivocations between Paris Hilton and Barack Obama from the McCain camp. Celebrity tends toward a certain degree of inevitable self-defeat, and the benefits don’t always outweigh the costs. Zizek seems to think that he can insulate himself from that self-defeat by, while making a celebrity of himself, writing about celebrity.

It seems to me that both Zizek’s horror and his success depends on his mixing the very two things you mention. I would describe Kirsch’s accusation, in terms of your two complains this way: Zizek got the first cheaply by doing the second.

Nathan: ” I would describe Kirsch’s accusation, in terms of your two complains this way: Zizek got the first cheaply by doing the second.”

Kvond: Hmmm. He cheaply earned celebrity. Isn’t hard-earned celebrity, (celebrity of the kind that he is accused of) an oxymoron? Isn’t the attack of “You are JUST a Celebrity!” an impunement of the process that lead to your fame?

Is there a thinker whose celebrity was earned? Rorty perhaps? Derrida? Now that they have passed, one might think that, but each of them struggled with the jealousy of what can only be called the phenomena of their ideas in society.

Secondly, your statement makes it sound like he was looking for celebrity from the beginning, and that he orchestrated it through “cheap” or “sensational” means. One might imagine this, but I am sure that Zizek never imagined what he has become.

Anytime an “expert” shows the ability to communicate to the “non-expert” serious things are afoot that need to be straightened out.

I agree with what you’re saying; again, I am describing what I think Kirsch’s position is, not my own. Actually, I suspect Zizek is able to tackle the important problem of celebrity as a thinker only because he has done so well at achieving it himself. Would that we had more celebrities doing interesting intellectual work.

But I also wonder whether you’re being a bit unfair with Kirsch as well. He has substantive complaints with Zizek’s work that are worth hearing out and carefully evaluating. I don’t think the review can be reduced to celebrity envy. If Zizek is doing something dangerous, his celebrity only makes it more so.

Nathan: “But I also wonder whether you’re being a bit unfair with Kirsch as well. He has substantive complaints with Zizek’s work that are worth hearing out and carefully evaluating. I don’t think the review can be reduced to celebrity envy. If Zizek is doing something dangerous, his celebrity only makes it more so.”

Kvond:If you recall, I did mention that there was another fundamental objection/warning: that Zizek was not horrified by the proper things. This is a substantial objection, and in fact one might even say that societal classification of individuals (and their ideas/beliefs), is fundamentally organized around THIS kind of objection. Whether or not you have the right ideas is not often settled by Idea-to-Idea confrontation (as rational as we would like to be about it), but rather, How to you respond in your GUT to imbued phenomena. Are your horrified at the right things? Are you warmed and tingled at the right things? The truth of the matter is that we most likely would accept people with the WRONG ideas (which we disagree with), if they are horrified and warmed appropriately, rather than the reverse. There are very good reasons for this, for our affective memories and communications work to conserve our relations in significant ways.

Now Zizek wants to challenge this very organization, the easy way that we all can be horrified and warmed by the same things. Such things in a society work in a fairly sacrosanct way (again, for good reasons). Now, some would say that his is only playing to a shock value which cheaply serves him. Others would say that if he is not horrified by the right things, then his ideas could work to make truly horrifying things happen. (Being horrified at THE Holocaust, for instance, works to admit one into a possibility of a humane, European future, i.e. one without Holocausts.) But because Zizek is interested in challenging the very substantive affective organization of our sense-making, political capacities, he cannot help but challenge some very important societal structures (structures that do not seem to be very important until you imagine their violation…). There is an imp of perversity in Zizek, the gleeful joy of pricking with small fingers the immense inflation of European and American political sensibilities. Arguing eloquently for what previously was a bit unthinkable, not because it was logically impossible, but because it was obviously and affectively not SO, is a form of intellectual judo he is quite good at.

The big question is, are these ideas parlor-tricks played upon the intellectual mind, the mind that thinks that Ideas themselves are the important thing, and not our affective investments? Or are these reversals into horrification, imagining the unthinkable as rational and cogent — Stalinism wasn’t so bad after all compared to the ideologically hidden brutalities of the West (?!) — instructive on some level, some very important level. These are big questions.

In a certain regard, the reaction to Zizek’s flirtation with the horrific is well-deserved. He wants to touch the very fabric of our sense-making skins, even to go into the wound-places, and he does it as a kind of Trickster. The wisdom about Tricksters and wounds is a careful one. Wounds are often the last place you want a Trickster playing around.

I do think though we need to pay attention to our REACTIONS to those who are not horrified and warmed to the right things.

Yeah, I remember. Recall that I discussed the two objections in my [December 2nd, 2008 at 6:54 pm] comment. It was only with [December 2nd, 2008 at 7:13 pm], when you turned to the issue of celebrity alone, that I wanted to emphasize the role of other aspects.

In some ways, it seems like Zizek is asking for responses like Kirsch. If he didn’t get them, probably he’d think he wasn’t pushing hard enough.

Nathan: “In some ways, it seems like Zizek is asking for responses like Kirsch. If he didn’t get them, probably he’d think he wasn’t pushing hard enough.”

Kvond: Very true. Actually, I read over at a Lacanian weblog that the article was “searing” or something like that. I was surprised to find how tame it was. I suspect that Zizek found it amusing, and perhaps wished it were a bit more vehement. He likely was happy to have found his place in such mainstream American political discourse, something that could be read on a Sunday morning with your Latte. Too bad he doesn’t write more interesting books. I think it was the weblogist k-punk who said that he is like a DJ who just mixes and remixes the same music. There is a bit of truth in this, once you get over the “shock” imagining the rationality of the “unthinkable”.

What is worse, Zizek is boring, or Zizek is dangerous.

[…] Ticker jake on Herzog’s Apocalypsekvond on Are Ideas Serious? (Zizek in Jonestown)Nathan on Are Ideas Serious? (Zizek in Jonestown)Nathan on In bed with Templetonkvond on Are Ideas […]